Even with all the scientific advancement in the study of addiction, there is still an overwhelming amount of misunderstanding and disapproval for those that struggle with the disease, especially alcoholism. A person battling alcoholism is often written off as someone who “can’t hold their liquor” like “normal” drinkers.

Fortunately, scientists continue to push the boundaries, broaden our understanding of the effects of alcohol on the brain, and seek an eventual cure for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

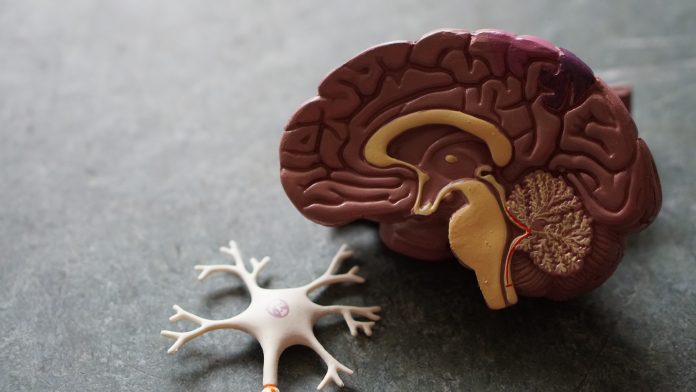

Areas that Alcohol Effects the Brain

In November, Salk Institute researchers announced that they discovered two areas of the brain that create a circuit, in mice, that controls compulsive drinking. Their findings, published in the journal Science, also include a method for forecasting whether or not the mice would develop compulsive alcohol-seeking behavior before it actually happened.

Their research may lead to advances in treating humans with AUD, as well as being able to predict if a particular person will struggle with addiction if they start or continue to drink alcohol or use other drugs.

“We initially sought to understand how the effects of alcohol on the brain

are altered by binge drinking to drive compulsive alcohol consumption. In the process, we stumbled across a surprising finding where we were actually able to predict which animals would become compulsive based on neural activity during the very first time they drank,” the lead author and assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology at Vanderbilt University, Cody Siciliano, told Salk News.

The study, funded with grants from the National Institute of Health, took a turn from previous research, which sought to observe what happens to the brain after a subject has developed an alcohol use disorder. Here, the research focused on areas of the brain that can provide warning signs before the disease of addiction develops.

Mice and The Effects of Alcohol on the Brain

The team of scientists, lead by Kay Tye, a neuroscientist, and professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences, created a protocol called Binge-Induced Compulsion Task (BICT) to see how different groups of mice would react to various stimuli, such as negative outcomes, in coordination with drinking alcohol.

Researchers were able to put the mice into three different categories, based on their behavior to BICT: low drinkers, high drinkers, and compulsive drinkers.

What stood out is how mice in the “compulsive drinkers” category showed little regard for negative consequences, much like a person with AUD who continues to drink despite the personal, professional, and social chaos associated with their drinking.

Using brain imaging techniques, researchers tracked the brains of mice before, during, and after alcohol consumption. They discovered interactions in two regions of the brain, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the periaqueductal gray matter, that predicted whether mice would fall into the “compulsive drinker” category on the very first drink the mice took. They were also able to manipulate these two regions of the brain with optogenetics, the use of light to control neural activity and make the mice drink more compulsively or less.

“We don’t know if this brain circuit is specific to alcohol or if the same circuit is in multiple different compulsive behaviors such as those related to other substances of abuse or natural reward, so that is something we need to investigate,” Tye tells Salk News.

Science Continues to Learn Alcohols Effects on the Brain

Though these findings are only conclusive in mice so far, they hold promise that science continues to advance the understanding of how addiction may be treated in the future and that this knowledge can lessen the stigma surrounding alcohol use disorder, a condition that according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, affects an estimated 14 million people in the United States.