Peer recovery group meetings are widely popular among recovering addicts and can be powerful tools in the road to sobriety for various reasons. However, limited research has explored how these social support groups function and what makes them work in addiction recovery.

On January 1, 2016, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) estimated it had a total of 2,089,698 members around the world and although Narcotics Anonymous (NA) does not keep an exact record of the number of people who attend meetings, they currently hold about 67,000 meetings a week in 139 countries.

“Trust and honesty are important, as is understanding that people’s experiences are both similar and different. Therapy led by professionals is, of course, important — maybe even more needed in many cases, perhaps particularly early in people’s recovery journey. But I suspect there is something about the ‘self-help’ bit that makes these groups so successful,” said Daniel Frings, a London-based social psychologist.

Frings was recently prompted, by the popularity of recovery group meetings and limitations in research, to conduct a study that offered a deeper look into the support provided by the groups.

“Group therapy is really prevalent — some work suggests around 80 percent of people seeking treatment for alcohol in the U.S. will encounter AA for instance,” Frings said. “We have a large number of people attending groups, and we have only a limited understanding of how they work from an identity perspective. Remedying this can potentially help us make groups better. For instance, understanding under what conditions people do well in groups, how group identity changes behavior in ways which we are sometimes not aware of, and how the group dynamics affect change.”

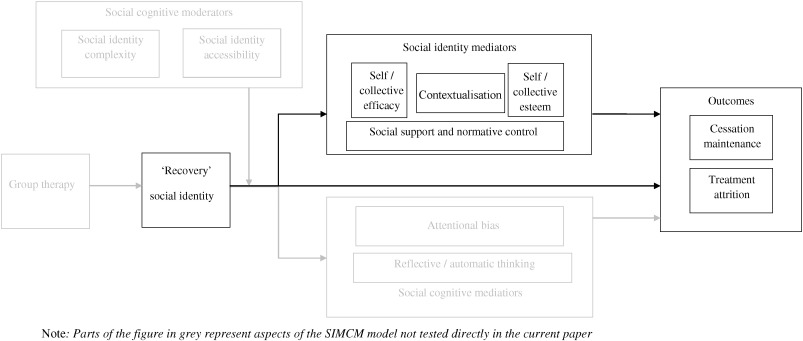

Frings looked into the dynamic of support groups for addiction recovery through a theoretical explanation of addiction cessation maintenance — the Social Identity Model of Cessation Maintenance (SIMCM), which essentially says that people who are trying to change their behaviors can rely on their social identities surrounding cessation for support.

Cessation, in the context of this study, was defined as the decrease in addictive behavior in the direction of (and including) complete abstinence. Supportive social control, Frings said, is a behavior that helps group members maintain their cessation. Most of the time it’s very inclusive but can also be exclusionary under certain circumstances.

A total of 44 participants from AA, NA, Cocaine Anonymous (CA) and Self-Management & Recovery Training (SMART), aged between 22 and 63, were asked to list the goals of their groups as well as the types of group behaviors they considered acceptable and deviant before they were asked to rate different responses to said deviant behaviors.

Participants reported several social triggers that provoked them to seek treatment, such as being perceived by society or referred to as an ‘addict’ or a ‘junkie.’ The participants’ goals were to stop using drugs and/or alcohol, get or stay sober, help others get or stay clean, and pass the group’s message around to other people.

The study also highlighted that one instrument of social control that has been used by members – particularly high-status members – of peer support groups like AA is criticism.

“When we started this line of research, we got a strong reaction from some members of the recovery community – ‘no-one gets thrown out of AA – ever!’ type comments. People got quite passionate about it,” Frings said. “Both new and established members find treatment groups an incredible source of support and, if you mess up, groups members usually want to help you through education or other support. The exception seems to be behaviors, which threaten the overall function of the group – inappropriate sexual conduct, violating confidentiality, things like that. Those behaviors attract more exclusionary responses.”

Costs of relapsing to the individual and to the group were… (continue reading)